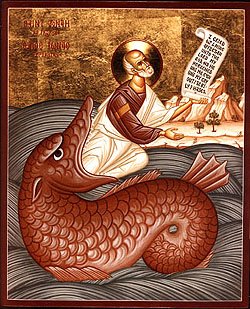

What Are We To Make Of The Sign of Jonah?

38 Then some of the scribes and Pharisees said to him, ‘Teacher, we wish to see a sign from you.’ 39 But he answered them, ‘An evil and adulterous generation asks for a sign, but no sign will be given to it except the sign of the prophet Jonah. 40 For just as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the sea monster, so for three days and three nights the Son of Man will be in the heart of the earth. 41 The people of Nineveh will rise up at the judgment with this generation and condemn it, because they repented at the proclamation of Jonah, and see, something greater than Jonah is here! 42 The queen of the South will rise up at the judgment with this generation and condemn it, because she came from the ends of the earth to listen to the wisdom of Solomon, and see, something greater than Solomon is here! (Matthew 12:38 – 42).

38 Then some of the scribes and Pharisees said to him, ‘Teacher, we wish to see a sign from you.’ 39 But he answered them, ‘An evil and adulterous generation asks for a sign, but no sign will be given to it except the sign of the prophet Jonah. 40 For just as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the sea monster, so for three days and three nights the Son of Man will be in the heart of the earth. 41 The people of Nineveh will rise up at the judgment with this generation and condemn it, because they repented at the proclamation of Jonah, and see, something greater than Jonah is here! 42 The queen of the South will rise up at the judgment with this generation and condemn it, because she came from the ends of the earth to listen to the wisdom of Solomon, and see, something greater than Solomon is here! (Matthew 12:38 – 42).In one of Jesus’ more interesting speeches, he tells us that the sign he will give to us to validate his ministry is the sign of Jonah. Following his initial remarks about the sign, Christians tradionally interpreted it as a prophecy of Jesus’ death and subsequent resurrection. While certainly correct, I have often pondered whether or not this answer is a bit too simple, and we have not fully understood what Jesus was telling us.

Indeed, what Jesus said about Jonah should tell us that there is more to the story than Jonah's journey at sea. Jonah had been given a warning to deliver to the people of Nineveh: repent or face destruction. Because they repented, the predicted doom did not occur. We do not see Jonah as a false prophet because what he said did not come to pass. He was a preacher of righteousness who understood the final consequences of sin. It is self-destructive. If it is left unchecked, it will destroy everything in its path.

Perhaps the sign should be seen within a holistic interpretation of Jonah’s life. It is not only his journey into the belly of the beast, into the abyss as it were, that we need to see as a sign of Christ, but also the final repentance of the people of Nineveh and God’s mercy towards them. Without Jonah’s warning, they would not have turned away from their wickedness.

In his ministry to the people of Israel, Jesus not only came as healer, but as a preacher of righteousness. His morality was the law of love. All other rules, all other regulations, come from the demands of love. Sin as a violation of God’s law is seen as a violation of the law of love. In his prediction of the Last Judgment, Jesus tells us that there will be two classes of people, those who lived out the law of love, the sheep, and those who violated its dictates, the goats.

Many people, when reading this prophecy, see it as if Jesus were giving us a glimpse of future history: what is said in it must come to pass. If Jesus says that there will be people sent to eternal perdition, then that is the end of all debate. Hell exists and people will be sent to there. If not, Jesus is a liar and we should not believe what he tells us.

However, are they reading this prophecy correctly? If Jesus gives us his life as the sign of Jonah, then perhaps, just perhaps, what he tells us about the Last Judgment should be read in this light. Jonah showed what sin does to society: Jesus tells us what sin does to the soul. However, he did not come to bring us a message of doom, his message was a message of hope, “I came not to judge the world, but to save it” (John 12:47b). Perhaps, like Fedorov, we can say:

…we dare to think that the prophecy of the Last Judgment is conditional, like that of the prophet Jonah and like all prophecies, because every prophecy has an educational purpose – the purpose of reforming those who to whom it is addressed; it cannot sentence to irrevocable perdition those who have not even been born yet. If that were the case, what sense, what purpose, could such a prophecy have, and could it accord with the will of a God, who, as already stated, wishes all to be saved, all to come to true reason and not to perish? -- Nikolai Fedorovich Fedorov, What Was Man Created For? The Philosophy of the Common Task. Trans. Elisabeth Koutaissof and Marilyn Minto (Lausanne, Switzerland: Honeyglen Publishing, 1990), p.129-30.

Looking at Jonah’s life holistically as a sign of Jesus’ own mission suggests that Balthasar’s daring hope for the salvation of all might indeed come to pass. We do not know the fate of the world. We have only been given possibilities. If it were a certainty that there are souls destined for eternal perdition, how could we pray, “O my Jesus, forgive us our sins, save us from the fires of hell, lead all souls to Heaven, especially those who have the most need of your mercy”?

Labels: Eschatology